Fine Arts Professor Liz Frey Weaves Art and Education

Fine Arts Professor Liz Frey Weaves Art and Education

What does true passion look like? One need only look to Centralia College Fine Arts Professor Liz Frey for the answer. Her love of creation – and her fiber arts medium – have taken her in fascinating directions and to exotic locations.

Frey was born into a creative and cultivating family. Undeterred by suburban standards, her artistic, animal-loving mother raised horses, goats, and chickens in their yard. She had her daughter sculpting and drawing from an early age. Both elements shaped Frey’s life in important ways.

Frey attended Hampshire College before transferring to Evergreen for their organic farming program. “I went through college in the middle of the 1970s’ back-to-the-land movement,” she said. “I had a very idyllic fantasy of living in the wilderness with a small group of friends, making our own community. I got really interested in that self-reliance idea.”

When she graduated with her bachelor’s in agriculture, Frey set about making her fantasy a reality. She and her partner purchased a farm and began cultivating their own rural haven. They grew a robust garden and raised sheep so Frey could craft clothing from their wool. “I did a lot of weaving and dyeing,” she said. “It was a really rewarding experience.”

But by the 90s, industry had already changed the game. Crafting fabric from scratch was no longer cost-effective, and the process was exceptionally time-consuming. “I lost steam,” Frey said. “It was too many things. I had to choose which part of the process to focus on and how I would make a living out of this.”

Frey adapted, focusing her efforts on weaving and creation. She sold her wares at art and craft shows, which eventually led to more elite events. However, the more she advanced, the higher the stakes. “Those take a great deal of investment,” she said. “The higher I got in terms of maybe getting a higher price for my work, the higher the investment became for the marketing. I’m not really a business person. It was frustrating. I barely made a living.”

Crafting a New Design

Crafting a New Design

Frey chose to evaluate and redirect. She considered several options, ultimately pursuing the one that spoke to her most. It was a bold course of action: earning her graduate degree in art from the University of Washington. It was, after all, her passion.

From the beginning, the school urged students to understand that this degree was about developing as an artist, not increasing earning potential. “They said, ‘We hope you’re not here to get teaching jobs; there are very few jobs in the arts and no teaching jobs in the fiber arts,’” Frey recalled, “but I said, ‘I’m going to do it anyway and hope for the best.’”

Frey threw herself into the educational experience, developing and enhancing her own artistic style. “I transformed from decorative and wearable objects to art that expressed something I felt and experienced and wanted to share with other people,” she said. “I began experimenting with fabrics that could be made structural by weaving in very thin wire, then folding and binding them.”

She became well acquainted with the Japanese art of Shibori, which is similar to tie-dye, and developed a project based on the elements of earth, air, water and fire. The program stretched her perceptions and improved her artistic expression. A visiting guest artist gave her particularly memorable feedback. “She looked at my fire work and said, ‘I’d like to see you go farther; push this,’” Frey said. “I told her, ‘I’ve used red and fire colors.’ But she said, ‘Why don’t you burn it?’ That opened the top of my head. I went to the metals studio and used torches under the exhaust fan hood. There was lots of smoke.”

From there Frey experimented with binding, etching, and burning fabrics with bleach and acid. “I’d create and destroy,” Frey said. “You’d unfold the fabric and there’d be patterns left: untouched, burnt, and full transition zones where it was decomposing. It expressed my interest in Buddhist thought. Creation and destruction are happening all the time. It’s a miracle; it’s coming from nowhere and it’s disappearing like soap bubbles.”

Weaving the Pieces Together

After graduation, Frey encountered a friend who told her about an adjunct position in the art department at Centralia College. It was a natural fit, and the job transitioned into a tenure-track position. “Don’t let them tell you there are no jobs out there or that your inner calling isn’t going to yield fruit,” Frey said. “You should follow your inner calling.”

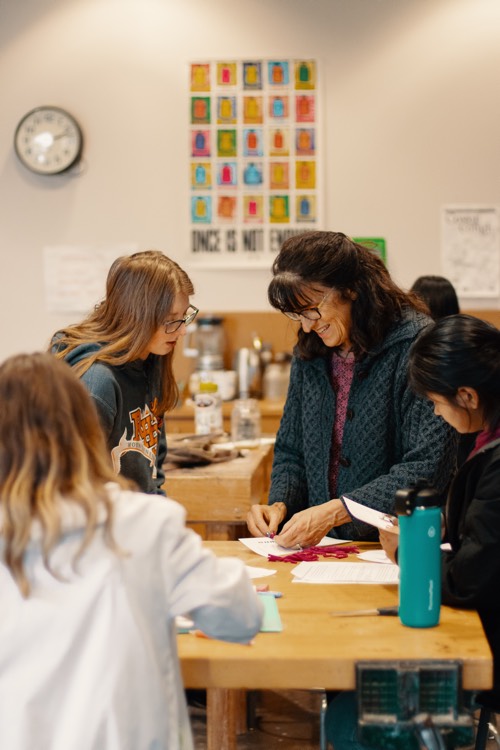

Frey has continued to hone and expand her craft at Centralia College, reveling in the joy of sharing it with her students and cultivating their individual talents. She advocated for and successfully implemented a thriving fiber arts program, making Centralia College one of the few in Washington to do so. “My experience at Centralia College has been really amazing because I continue to learn and grow all the time,” Frey said. “I expected art history to be boring – just going over the same material again and again. But every year I go over the material with a deeper understanding.”

Centralia College has supported her – and the rest of the Art Department – every step of the way. “They support our efforts to provide inspiring and relevant art experiences for students,” Frey said.

An Elaborate Tapestry of Experience

Frey incorporated a DVD entitled A Century of Color: Maya Weaving and Textiles into her class. Intrigued by the program, she made a point of writing and thanking the creators for this educational tool. She also asked if further efforts were underway that she might assist with. As luck would have it, they were in the process of beginning an Endangered Threads documentary in Guatemala.

She took a sabbatical and traveled there with her husband Robert and daughter Ana, who Liz had adopted from Guatamala in her infancy. While Frey assisted the documentary crew, the family dove deep into their daughter’s ancestral culture. It was thrilling.

The family climbed ancient temples buried deep in the rainforest while spider monkeys swung in nearby trees. They interacted with locals and experienced the culture of Guatemalan fiber arts firsthand. And they got a flat tire on a deserted high-mountain road. “My husband changed the tire lying on his back in the mud,” Frey said. “It was really a wonderful adventure.”

Frey has since collaborated with Spanish instructor Mark Gorecki to take a class to Guatamala to study Maya art and culture. The experience still informs her work today. She uses all-natural dyes and ethically-sourced fibers in her work and classes. It’s both an homage to weavers of the past and an act of cultural responsibility. “Know where your textiles come from,” Frey urges. “The fabric industry is among the top handful of polluters in the world. You have to consider everything from the pesticides and herbicides used to grow cotton to the chemicals used to process them, like bleach.”

Frey is combating this as a supporter of the Slow Fiber Movement, which takes its name and concept from the Slow Food Movement. “They connect people who grow fibers and dyes with people who create textiles,” she said. “Developing local, natural sources for our fabrics is an important part of creating a sustainable economy. I’m really interested in natural fibers. We use wool and cotton in class. I teach how to dye with natural dyes that are harmonious with the earth.”

She currently has a few exciting projects on the horizon, largely centered around natural themes. “I want to make big trees,” she said. “I’d like to weave wire into the fabric, then squish and dye it. Then, when you open it back up, you can see the woven patterns on the inside when you get close. I’d create textures, all rough on the outside like bark, and interesting patterns on the inside.”

After a long career in fiber arts, Liz Frey’s passion still burns strong – and Centralia College is fanning the flame.